A tinkling, slightly out-of-tune music box plays and a monochrome picture of an eye stares out of the screen, brown on sickly yellow like a peeling illustration on a nursery wall, but as we back away from it we see that the human eye sits in the face of a doleful teddy bear listlessly propped up on a mantelpiece. We back away still further until the picture shows us a little girl, back to the artist, sitting and (we imagine) looking up at the teddy. Except that when the figure of the girl rotates, her eyes and mouth have been stitched together.

Draw your own conclusions about the provenance of the teddy’s long lashes.

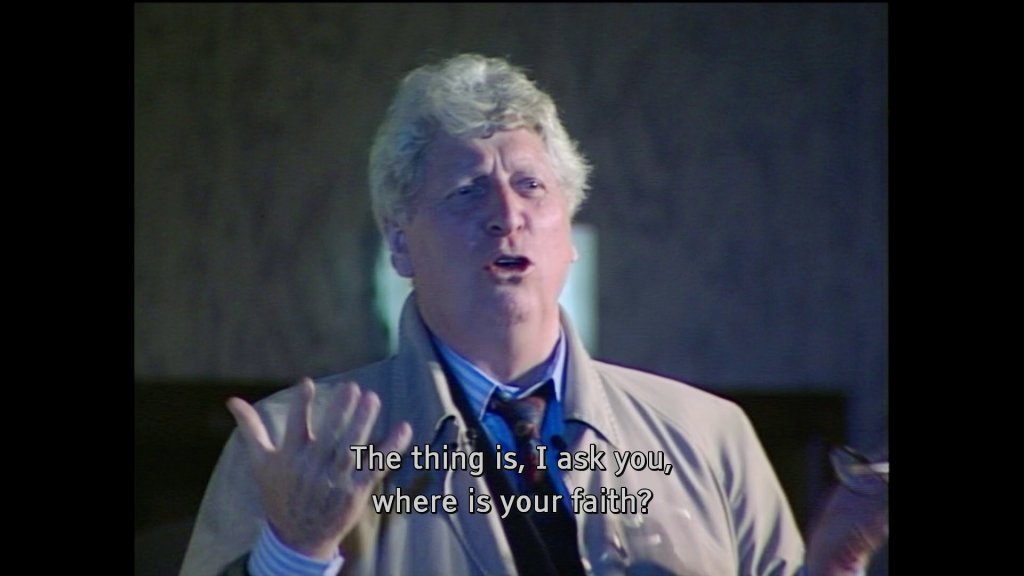

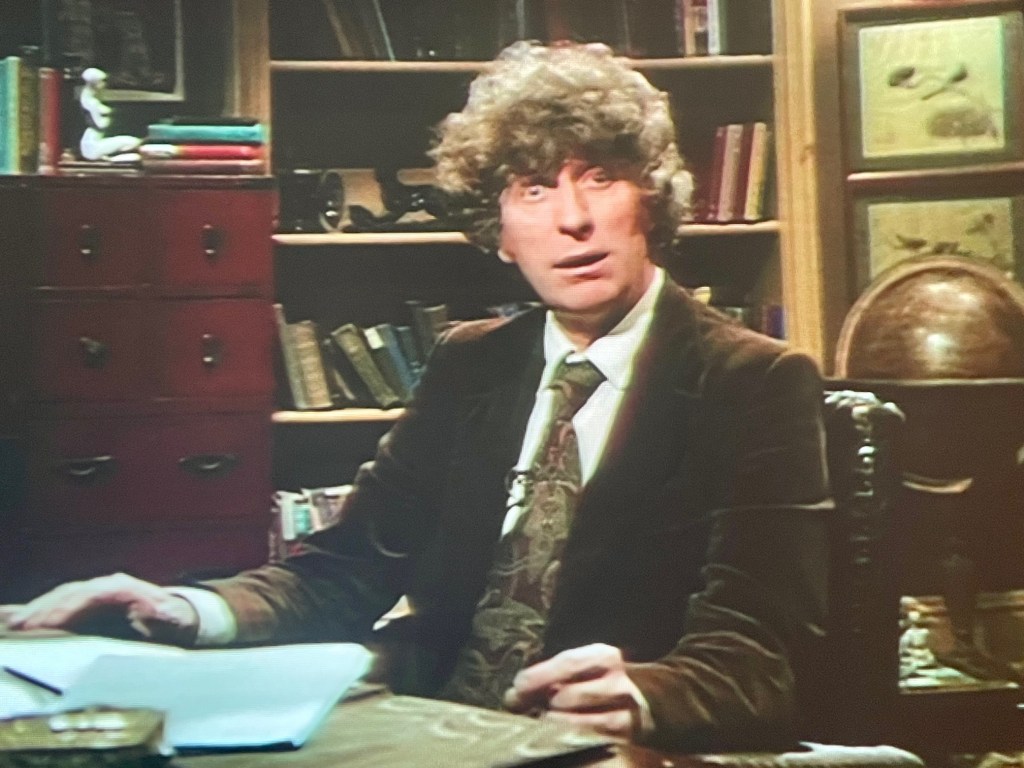

The macabre juxtaposition of the childlike and the grotesque neatly sums up the yarns chosen for Late Night Story (on The Armageddon Factor, part of The Key to Time DVD box set), a series read by Tom Baker in 1978. He sits in a study, surrounded by bookshelves, cabinets, a chess set, a globe, almost as if he has arrived on the set for Professor Chronotis’ rooms a year early. Lit with a warm, autumn-evening hue, it’s basically a comforting picture; and that’s Doctor Who off of Disney Time, isn’t it? In his brown jacket he might as well be – he looks pretty much as he did after abandoning the scarf in Robots of Death (and in some episodes he also wears a paisley tie, anticipating a later Doctor). Then he eyeballs the camera, something playing around his face that might be a smile waiting to get out but that might also be a dreadful howl like the one he emits in Terror of the Zygons, and he tells stories. It’s like Jackanory, if children’s television had ever set out to traumatise an entire generation in one go.

Above: Tom Baker on Sunday 3rd August 1975 in the Odeon ‘Disney Cinema’, St Martin’s Lane, London, during filming of his links for Disney Time. Colourisation by Clayton Hickman, without whose wonderful, wonderful work a series of blogs about Doctor Who would be a little bit unseemly.

The stories all involve children – or people acting like children. There’s a sad little tale about an ill child by Nigel Kneale, a nightmarish party game in a story by Graham Greene and a stories by Mary Danby and Ray Bradbury that go for slightly more unrestrained horror. Perhaps best of all there’s a chance to hear Saki’s deliciously venomous masterpiece Sredni Vashtar, which didn’t even get broadcast. It’s a really fine selection of stories, all of them possessing a sting in the tale which in many cases lingers long after the talking is over (the awfulness of Graham Greene’s The End of the Party only sinks in as the credits are rolling over that creepy music box and Tom is already back to work at his desk as if nothing has happened).

Baker gives the tales an electrifying intensity, his eyes twinkling dangerously, his face never quite deciding whether what he’s saying is amusing or horrific, a chilling detachment that is matched by his delivery of the prose. He has an expert sense of pacing, eliding sentences in a way that is characteristically Tom Baker and pausing just occasionally to let an image sink in. He speaks the dialogue with cold humour, perfectly capturing the no-nonsense tone of the soppy stern adults and giving the younger characters an authentic innocence which is either helpless or morally bankrupt or both.

This is brilliant stuff. It is a reminder of the power of pure, unfussy storytelling, relying almost entirely on the person talking. There is little to hide behind – Baker delivers minutes on end to camera in a single shot, broken up by the occasional change of angle or slow zoom, but nothing to distract from the twin stars of the show: the writing and the storyteller. It is something television lost long ago – even Jackanory when I was growing up had started to rely a little too much on crude animations of illustrations, diluting the compelling simplicity of the spoken word (I understand that when the programme briefly came back in 2006 is was with elements of CGI, so as far as I’m concerned that can get in the sea). And television now, with is slavish desperation to be ‘cinematic’, has all-but forgotten the power of a single shot framing a brilliant performance, something that TV of yesteryear did out of necessity but which is sadly lost to children and adults alike, bar the odd Talking Heads (Bennett, not Byrne) or Mark Gatiss’ 2017 anthology Queers (if you didn’t see it, search it out).

In the 1970s, a time of storytelling par excellence, they caught Tom Baker at the height of his powers doing something to rival even the great Bernard Cribbins. And Cribbins would never have been this scary: Tom may be dressed as the Doctor, but if the fourth Doctor had been anything like this then the other Baker would not be the one saddled with the ‘darker persona’ label. It is perhaps my favourite Tom Baker performance ever and, curiosity though it is, is an example of the kind of peripheral material that we are fortunate enough to have turning up on Doctor Who home media releases. Nestling at the bottom of a long, long list of special features, it is nevertheless the best special feature ever. For all of the above reasons I have no compunction about stating that with absolute authority, even though I haven’t watched all of the other ones1.

- What? I had the audacity to make a top 10 without conducting exhaustive research?!! Yes I did. And I will feel no shame unless everyone who voted The Dalek Invasion of Earth the best story of the Hartnell era can prove they have listened to The Myth Makers. ↩︎